Ed Leonard

Behind Barbed Wire: A POW's Story

I arrived at Udorn RTAFB in early May, 1967, to fly A-1E and A1-H Skyraider with the 602nd Fighter Squadron (Commando). I was to fly 247 combat missions during three consecutive tours and participated in the rescue of 18 aircrew members. On May 31, 1968, going for number 19, I was shot down on a Search and Rescue effort for a Navy A-7 (Streetcar 304) flown by Kenny Fields. I ejected and, once safely on the ground, I got in a gun fight with three NVA soldiers. I shot one for sure3 AKs vs. one 357 seemed like a fair fight to me. I had them outnumbered! I got away and, after running most of the night, I climbed up a tree and hid there.

I arrived at Udorn RTAFB in early May, 1967, to fly A-1E and A1-H Skyraider with the 602nd Fighter Squadron (Commando). I was to fly 247 combat missions during three consecutive tours and participated in the rescue of 18 aircrew members. On May 31, 1968, going for number 19, I was shot down on a Search and Rescue effort for a Navy A-7 (Streetcar 304) flown by Kenny Fields. I ejected and, once safely on the ground, I got in a gun fight with three NVA soldiers. I shot one for sure3 AKs vs. one 357 seemed like a fair fight to me. I had them outnumbered! I got away and, after running most of the night, I climbed up a tree and hid there.

On the third day, Kenny was finally rescued, but I was spotted and captured. I was taken prisoner by a badly mauled North Vietnamese division dragging itself out of South Vietnam and moving northward through Laos following their defeat during the Tet Offensive. This was a problem for both sides. You see, we were not bombing Laos--we said so. And Ho Chi Minh's army was not in Laos--he said so. I was an embarrassment to both governments, a long way from home, and a bullet cost twelve cents.

After an initial interrogation, I was force marched each night for a week through bombed jungle. At last I was herded into a cave where I spent the day. At dusk, I was put on a truck, and was bolted, face-down, to the bed. All night the truck would jar, bumble, and roll, side to side, fore and aft, and up and down, like a repetitiously interrupted corkscrew. After stumbling into the morning, we at last came to a halt several hundred yards off the road, under trees and camouflage netting.

Periodically, the truck would stop on the edge of a village. Id be off-loaded and my arms bound behind my back, then Id be pulled by a noose about my neck through the village, through an inevitable gauntlet of angry villagers armed with clubs, jabbing sticks, and rocks, all whipped to a frenzy by a small band of political organizers. Once through the village, Id be put back on the truck, and once again wed bumble and stumble through the night.

Near sundown each evening, the truck would start off again for another bone-jarring night along rough bomb-cratered roads and rocky stream-beds. After a week, I was off-loaded on the edge of a broad valley and marched several miles across rice paddies to a wooded jungle rise. Under the tree canopies were bamboo cages, containing American servicemen and civilians, a number of Canadians, and a German nurse. I was placed in a bamboo cage removed from the others.

The second evening in camp, the other prisoners were taken out of their cages and moved out. Shortly after, two guards opened my cage and motioned me out. I was led down a trail and emerged on the edge of a large open field. There was a small creek meandering to one side and I could see the others bathing in it.

My guards stopped me a short distance upstream from the others and indicated I was to wash. The muddy water was waist deep and, after two weeks, I definitely needed a bath.. The sun had been down for some time, but the sky to the West was still slashed with bands of red and orange.

Even the guards appreciated the sight. I turned my head at the gentle sound of gurgling water. A head emerge from the murk:

"I'm Paul Montague, Captain, United States Marine Corps, the Senior Ranking Officer. Who are you?"

"I'm Ed Leonard, Captain, U.S. Air Force. "

"What's your date of rank?" he asked

"December '64".

As his head sank back into the water he said,

"Now you're the Senior Ranking Officer--you poor son-of-a-bitch."

I spent a total of three and a half years in solitary, during which I had many opportunities to reflect upon Paul's remark. Our duty as prisoners was to escape, to resist all attempts by the enemy to exploit us for propaganda, and to give each other whatever help and comfort we were able to provide. We had a tight organization in the camp.

Although told often there was no rank, whenever the enemy discovered our activities, the instigator and I would be called upon for some form of penitence--inevitably painful.

That autumn, we moved to Duong Khe, an old French military post some twenty miles outside Hanoi--our battlefield for the next two years. The buildings were concrete with interior rooms of varying size. If you've seen the movie "Papillion" with Dustin Hoffman and Steve McQueen, you've seen the place. The French built them all over the world. Here I was segregated from the others. Those captured in Laos were held in a separate part of the camp--very ominous. The others, mostly enlisted ranks, had been taken in South Vietnam. In all, there were 87 enlisted, 12 officers, and 7 civilians. I was moved away from my enlisted men (78 soldiers and marines captured in South Vietnam and Cambodia during the Tet Offensive) about a year before release. They put me in with seven others also captured in Laos. We were called the LULUs, the Legendary Union of Laotian Unfortunates.

As a rule, the officers and senior NCOs were held in solitary, but, using the tap code, we were able to establish good communications between cells in the building within a few days, and within a few months, to the other buildings in camp.

One morning, eighteen months after arriving at Doung Khe, the door to my cell opened and Paul was lead in. We were out of solitary! For the next three days, we both talked steady streams, after that we started, occasionally, listening to each other. Paul, a career Marine, was deeply concerned for his family; he had no way of knowing if his wife and children had been informed of his capture. He would have been unhappy to learn he'd been killed in action.

Paul had already seen the depth of hurt prolonged separation had inflicted upon his daughter. Some years before Vietnam he'd returned home from an eighteen-month, unaccompanied tour of duty in Korea.

He'd arrived on a Friday afternoon during the school year; had a wonderful reunion with his family. Monday morning, at breakfast, his daughter, then in first grade, eagerly went to work on him.

"Daddy, will you meet me after school and walk me home?

"Sure, Pam, just tell me where."

Whereupon Pam produced a very detailed map, showing how to get to school, the main entrance, and a big red "X" next to the flag pole

"You won't forget, will you, Daddy?"

"No, Pam, I'll remember."

Daddy, will you wear your uniform?"

"I really don't want..."

"Please, Daddy, Pulleesss..."

Shirley chimed in, "Wear it, Paul."

So it was settled, and Paul, in dress uniform, left the house shortly after three, arriving at the flag pole as the school bell rang and a horde of children disgorged from the front door.

But, no Pam. Paul waited, impatiently at first, then a bit anxiously. He checked his map...there was no mistaking the crayon drawing, he was where designated.

Finally, as the playground cleared of the initial wave, Pam appeared, accompanied by half a dozen of her little friends. Spotting her father, she tossed her head triumphantly and arched directly toward him, her friends straggling sheepishly behind. Arriving a short distance in front of Paul, she stopped, spun about, and putting her little fists to her hips, half shouted at the other children in a voice trembling with anger and pride:

"You see, I do too have a Daddy!"

Imagine listening to Paul, a ragged, starved scarecrow of a man, sitting in the gloom of a prison cell telling me this story of his daughter, ten years earlier. How must Pam have felt during her fathers Memorial Service? Did she remember her defiant cry, "I do too have a Daddy!"? (Paul was repatriated with me and now lives in Kansas with his wife, Shirley.)

The over-riding emotion of prolonged imprisonment in solitary confinement is boredom. The first time you are in solitary it takes roughly two weeks to establish a routine. First thing in the morning is a prayer followed by some exercises then sitting on the floor letting the mind wander. Boredom sets in and you walk inside the cell. Keep your eyes on the crack under the door since you are required to sit on your mat and not move. Any guard approaching will cause a slight shift in the light under the door giving you enough time to get to your rice mat and sit down. Eyes on the crack quickly became a way of life. With time various events are added. The exercises quickly become the daily dozen. Dozen indeed...it became fifteen. And rather than one set in the morning it became fifteen sets of fifteen.

The Morning Prayer became a church service with hymns and the Apostles Creed interspersed with bible passages memorized years before in Vacation Bible School. After church, another set of the Daily Dozen. The highlight of the morning was The Count. How many days before Labor Day? (Sing Ive been working on the Railroad.) Days till Suzannes Birthday? (Sing Happy Birthday to her) Days till Halloween? (Sing Caspar the Friendly Ghost) Each holiday and family birthday had its song. After The Count it was time to get the mail ready for delivery. This had to be done in case the honey bucket detailwe called them the Pony Express or just simply the Poniesarrived early. After prepping the mail it was time for another set of the Daily Dozen. Once this was done itwas time for Story Hour. Story Hour consisted of telling myself a story which I made up as I went along. I particularly enjoyed the trialsI argued both sides and added evidence when my argument on one side or the other became thin. I also ran a cattle spreadId spent some time with a Marine officer who grew up on a ranch and he gave me a few pointers. Being a rancher was a delight, as I spent most of my time outdoors. Winters on my ranch, especially the heavy snow, coincided with the hottest of days. I was also a surgeon, but had to defend myself when I killed a couple of patients. Then another set of the Daily Dozen.

Story hour was usually interrupted by the approach of the Ponies. A guard would unbolt my cell, open the 3 thick wooden plank door, point at my Honey Bucket, and grunt. (The guards were not permitted to talk to ustheyd all read a Vietnamese translation of The Great EscapeAmericans were not to be trusted.) I'd place the bucket outside and return to my cell. The guard would shut me in and bolt the door. Shortly thereafter eight of our junior enlisted would arrive with four Vietnamese guards. The junior Vietnamese guard was tasked to inspect the inside of each bucket to insure we were not passing notes.

Unless you were being punished, you were taken out to wash by the well twice a week. This was a highly dangerous time since it was necessary to tend the message drops, both delivering mail and retrieving it. After washing, you would wait for your first meal of the day, a watery soup and a small lump of wheat bread, usually containing rat feces. Four summer months meant watercress soup. The four fall months meant pumpkin soup and winter brought cabbage soup. Variety was not part of the menu. The guards would put out four bowls of soup and four pieces of bread. I always hoped to be the last prisoner to retrieve the food. Otherwise there was a moral dilemma. One lump of bread always looked bigger, one bowl a bit fuller. In fact, differences were infinitesimally small, if they existed at all. A dent in the bottom of a bowl gave the illusion of fullness, an air bubble in the bread made it appear larger. If I took the larger portion, I suffered shame for days. If I took the smaller portion, the pains of starvation seemed trebled. If I was last to collect the food, I avoided the moral issue until the next feeding.

After the noon meal the guards would lock us in and then entire camp would sleep. After the naps, Id do another set of exercises followed by a walk until the evening feeding. After the last feeding, wed be locked down for the night, which meant another set of exercises and patriotic hour. Patriotic hour consisted of singing the national anthem, reciting the Pledge of Allegiance, singing the Air Force song, and reciting the Code of Conduct. (Yes, I remembered it from freshman knowledge. I was able to write it down and keep three copies in circulation in the camp. I used rough brown toilet paper and blood for ink.) More exercises were followed by evening church services, and then Id sit quietly letting the mind drift wherever it wished to wander.

All the while keeping an eye on the crack under the door.

I was doing a hundred finger-tip push-ups during each exercise period and fifteen periods a day. After about three years I became curious to see how many pushups I could do in a day. Slowly I built up to 2,700. At that point I noticed I could no longer hold the spoon to feed myself soup. I dropped back to 1,500 push-ups a day and was soon able to use a spoon again. Such is the nature of boredom.

Occasionally I would be taken from my cell to either be read a very long, boring piece of propaganda or interrogated about some activity in the camp (these were inevitably painful affairs lasting several days...or weeks). I bitterly resented these interruptions. Didnt they know I had things to do? I would be out of sorts for days and sometimes weeks trying to reestablish my routine.

In the summer of 1969, George McKnight and John Atterbury, prisoners in another camp, managed to escape; but were recaptured three days later. During their punishment, Atterbury died a horrible, excruciating death. The other camps had been notified of the escape and extreme security measures were instituted. Intense and torturous interrogation of all Senior Ranking Officers in the various camps, along with those individuals identified as hard core resistersthose most likely to be involved in escape plansresulted in a nightmarish, Kafka-like scenario.

The North Vietnamese tortured to confirm their worst suspicions. Driven beyond the ability to resist, prisoners "confessed" in order to end torture. Truth was not a factor in that ugly equation. Even when broken, you "confess" slowly, starting with "I was rude to the guards". When that did not result in reliefyou see how the torturer is teaching the prisoner what is wanted? You gradually increase your confession, first to stealing food, and then to communicating. ...and finally, with time, you confess to an attempted escape. This brings no relief. "And now, we will forgive you, when you tell us with whom you were going to escape."

The descent into pain and insanity is slow, a slow and excruciating immersion. You find you are implicating fellow prisoners in an escape plan that doesn't exist. How can you possibly come up with a satisfactory answer? The solution here was provided by the worst fears of our captors. You see, they had already decided which prisoners were most likely to be involved in an escape.

Over the course of weeks of unending torture, through the fog of pain and insanity, each prisoner was taught which names were acceptable to the torturer. This process resulted in identifying four of us.

"And now, we will forgive you.....as soon as you tell us how you were going to escape." The fog of insanity continued. This time, our captors could not teach us the answer. We were in separate locations, unable to communicate. To end the torture, we had to confess to the same method. The fog thickened. We had all been broken weeks earlier, but the torture went on, seeking an answer which did not exist. It as been repeated endlessly that at last the human spirit will reach bottom; how often do we hear "When they reach the bottom...." There is no bottom. There is no escape. It was during this period that I would periodically be able to escape by floating up at the ceiling from which I could look down and watch what they were doing to my body down on the floor. It was really disgusting. The first time I floated to the ceiling I was curious, but when it happened again, I became indifferent to what the guards were doing. Sometimes, when the guards were out of the room, my daughter, Tracy, would visit me. Shed sit at my feet and softly say, That's alright, Daddy...thats alright. I found this extremely comforting and I looked forward to her visits.

Ho Chi Minh died on September 3, 1969. Administration of the POW camps was immediately transferred from civilian to military control. Brutality and torture were immediately halted. Food and water were restored and sleep was allowed. Six months later, I was able to get to my feet without help from the guards. It has been nearly forty yearsand I still need to brace myself against a chair or corner as I stand.

In the spring of 1971, the enlisted men and pilots who had been captured during Tet and now being held as POWs in Plantation Gardens were ushered outside one evening. Fresh air and sunshine were a welcome treat, but the Americans watched with curiosity as the NVA guards rigged up a makeshift movie screen, draping a bed sheet over a clothesline. They were astounded to watch a 16 mm film of a long-haired young man with a long face, wearing medals on his fatigues as he testified before the Foreign Relations Committee that Americans had committed atrocities in Vietnam. More than one POW stood open-mouthed in astonishment, shocked that a fellow American military man would say such things in public, much less in front of Senator Fulbright's committee. Officers and enlisted alike were furious that this punk, a young Navy man on active duty, would make up lies like that, sounding as though he were running for office and this was a political speech. Surely, surely, he knew that his remarks would be pounced upon by the NVA and used in their propaganda!

I was the senior ranking officer at the Plantation Gardens and I realized something had to be done to prevent complete demoralization. By now, all the POWs knew about the Ducks, thirteen other Americans kept separated from everyone else, who received special treatment because they were informers and collaborators. In August of that year, I finally had the opportunity to address the issue, when I was standing outside my cell just as guards brought the Ducks out, roughly fifty yards behind me. I stood at attention, executed a smart about-face, and yelled that they were "to stop all forms of cooperation and collaboration with the enemy." My cellmates and I were quickly hustled into our cell, and a few minutes later guards came to get me. I was beaten into unconsciousness, and when I finally came to, roughly three days later, I could not feel my body from the waist down. This lack of sensation continued for a week, followed by searing, debilitating pain for several months afterward. But my stand had its desired effect; five of the Ducks changed sides, much to the other POW's delight. I was repeatedly beaten and accused of being a war criminal, and constantly reminded that a fellow active duty American military officer had testified to that fact.

I was the senior ranking officer at the Plantation Gardens and I realized something had to be done to prevent complete demoralization. By now, all the POWs knew about the Ducks, thirteen other Americans kept separated from everyone else, who received special treatment because they were informers and collaborators. In August of that year, I finally had the opportunity to address the issue, when I was standing outside my cell just as guards brought the Ducks out, roughly fifty yards behind me. I stood at attention, executed a smart about-face, and yelled that they were "to stop all forms of cooperation and collaboration with the enemy." My cellmates and I were quickly hustled into our cell, and a few minutes later guards came to get me. I was beaten into unconsciousness, and when I finally came to, roughly three days later, I could not feel my body from the waist down. This lack of sensation continued for a week, followed by searing, debilitating pain for several months afterward. But my stand had its desired effect; five of the Ducks changed sides, much to the other POW's delight. I was repeatedly beaten and accused of being a war criminal, and constantly reminded that a fellow active duty American military officer had testified to that fact.

On February 12, 1973, after the signing of the cease-fire in January, the first contingent of our 143 American military and civilian POWs departed Hanois Gia Lam Airport for the Philippines. During the following weeks, the remaining 444 were released. The LULUs, which Hanoi claimed were being held by the Laotian Communists, were among the last to be released.

It is perhaps in the ordination of Providence that we are taught the value of our liberties by the price we pay for them.

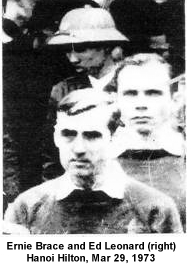

Homecoming, 1973: Ed Leonard, his sister, Karen Ray, and their parents