Bill Kornitzer

Mission to Iran: Desert One

I first became involved with the Iran hostage rescue mission in the fall of 1979, while I was serving as the Deputy Director of Operations for the 437TH Military Airlift Wing at Charleston AFB, SC. The Wing Commander and I were briefed on a possible mission to Iran to secure the freedom of American hostages being held in Tehran. At this time Charlestons C-141s were providing domestic airlift support for the Army Ranger and Delta Force personnel who would be the main forces involved .with the mission.

In January 1980, I became Director of Operations. Because of the number of people (hostages and their rescuers) to be extracted from Tehran had increased to approximately 330, the MAC Assistant Director of Operations made a rare visit to Charleston to personally brief me and our selected crews on an expanded role for our Wing. This number included 53 hostages, 120 in the Delta Force team, 100 Rangers and as many as 56 helicopter crew members that would have to be extracted out of Manzariyeh, Iran. This airfield was a few miles south of the American Embassy in Iran.

Training:

In January 1980, we selected our most capable and highly qualified crew members to fly the mission. I personally briefed them on the importance of security and told them that I only wanted volunteers for this mission. As one would expect, I ended up with [number] highly motivated and capable crews. We started our blacked out landing training with night vision goggles (NVGs) at North Field, which was a small satellite base north of Charleston. This mission was very sensitive and its success hinged on total security. We took extraordinary efforts to keep this mission known only to the crew members involved and the people needed to support us. In fact I was not allowed to brief the Wing Commander on our specific role and I carried orders from the Commander of MAC that required the entire Command to support my request no questions asked, period!

After our training at North Field, we did more extensive training at an abandoned airfield in Florida. The crews were doing real well and getting used to NVGs. I then took our crews to an extensive training session at the Tonopah Range in the vicinity of Nellis AFB, Nevada. After this training, I declared our crews ready to perform low level flight operations in blacked out conditions, no radio calls; and using only NVGs to land in total darkness. This was a first for MAC crew members in large jet aircraft. Of course, the MC-130 crews at Hurlburt Field were capable of doing this, and would be used to insert the Delta and Ranger Forces at the Desert One initial landing site.

Joint Training:

After we were qualified to perform at night, we participated in numerous dress rehearsals with the MC-130, AC-130, KC-135 and RH-53 crews and the Delta and Ranger Forces. These exercises included mock surprise night assaults on active duty bases in the US and then departing before day break. These exercises were monitored by high ranking officers from Washington to insure we were capable of doing the tasked mission. After we had successfully completed numerous exercises our Joint Task Force (JTF) Commander, Major General James B. Vaught, U.S. Army declared us ready to go and briefed the Joint Chiefs of Staff and, after that, President Jimmy Carter.

Deployment:

ON 18 April 1980 I was picked up at Charleston and flown to Andrews AFB in Washington. I departed Andrews AFB with General Vaught and the rest of the JTF staff. We arrived at Wadi Kena, Egypt, at 0230 AM on 20 April 1980. I was the COMALF [Commander of Airlift Forces] and all MAC resources supporting the mission were under my command, as directed by the MAC Commander, General Dutch Huyser. We set up schedules, met and briefed crews, and assigned aircraft for missions, etc. On the first day of deployment for the actual mission, I flew with my crews to serve as the MAC on-scene commander at Daharan, Saudi Arabia and then to move forward to the extraction area at Manzariyeh, Iran as the mission progressed.

During the period 20-22 April, all the forces that were to participate in the mission arrived. On the 23 and 24 April all the forces would start to move forward. The MC-130's, EC-130's [ fuel carriers], and Delta force would go to Masirah, Oman. These aircraft would all leave Oman on the 24th to meet up with the RH-53 helicopters at the Desert One site to refuel the RH-53s and transfer the Delta teams to the helicopters for their forward movement to the Tehran Area. I departed on the 24th for Daharan, Saudi Arabia. Our mission was to leave Daharan on the night of the 25th to arrive at Manzariyeh, Iran 10 minutes after the airfield was secured by the Ranger force. We would carry highly qualified medical personal, including surgeons, to treat the injured.

At Daharan, the Saudis would not let me offload anyone except crew members unless I let them inspect the aircraft. I refused, because we had weapons, secure radios, medics, Army personnel, etc. We were pretending this was a normal MAC mission into Daharan and nothing else. A few of the crew members went with me to the hotel to set up our secure satellite radio to monitor the mission and to get our final orders, We were only there for a few hours when we got the word the mission had been aborted. A minimum of six fully operational helicopters were needed to transport the Delta force to a holding area near Tehran in order to have a force deemed capable of success and only five helicopters were available out of the eight that departed the aircraft carrier the Nimitz in the Persian Gulf.

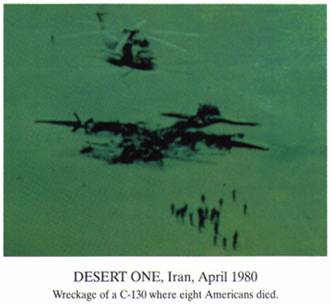

Shortly after we learned that there had been an accident between a RH-53 and a refueling C-130 at the Desert One site. There were eight deaths and numerous injuries. We were told to leave Daharan immediately and fly to Masirah to pick up and treat the injured. We did that and then brought the injured and the Delta Force back to Wadi Kena. The injured, including burn victims, were transferred to MAC Medevac aircraft and flown to Germany.

I stayed at Wadi Kena till late on the 26 of April, supervising the remaining MAC aircraft and crews as we loaded all remaining personnel and supplies and flew home. I was awarded the Defense Meritorious Service Medal for my role in the operation.

Aftermath:

This was a very disappointing outcome for all of us who had worked so long and hard to make it a success. It was devastating to lose eight crew members in an unfortunate accident and have to leave them behind. One remarkable thing about this mission was the scope i.e. the distances and the amount of forces that had to be involved. It was also a tribute to every one that this vast operation was kept a secret.

Today:

I later became the commander of all Air Force Special Operation forces at Hurlburt Field, Florida, as the 2ND Air Division Commander. Today Special Operations qualified aircrews and maintainers are better equipped and trained then we ever have been to conduct sensitive and highly covert missions.