Bill Goodyear

Mission to Katmandu

This is a story of royalty, romance, and death. Oh, yes, and flying. The events described took place thirty-six years ago, in a far- off corner of the world. They are recreated here from the combined memories of three of the actual participants.

Background

in July 1941, American President Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Churchill met for the first time off the coast of Newfoundland. Their objective was to issue a joint declaration on the purposes of the war against Germany. Just as Wilson's fourteen points delineated the first world war, so the Atlantic Charter provided the criteria for the second.

The first three articles read:

First, their countries seek no aggrandizement, territorial or other;

Second, they desire to see no territorial changes that do not accord with the freely expressed wishes of the peoples concerned;

Third, they respect the right of all peoples to choose the form of government under which they will live; and they wish to see sovereign rights and self government restored to those who have been forcibly deprived of them;

The third article lead to the disestablishment of the British Empire and the withdrawal of the French from Indo-China, where they had ruled over Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos for a hundred years.

In 1947, India was given its freedom from Great Britain. The French did not leave South East Asia until after their defeat at Dien Bien Phu in 1954. According the Paris Accord which terminated the French occupation, the Viet Minh took control of the northern half of Vietnam until national elections could be held. However, it soon became apparent that if national elections were held the Communist Viet Minh would gain control of the entire country. This was unacceptable to the United States.

The primary foreign-relations goal of the United States after World War II was to contain the growth of international Communism. Three strategies were being pursued.

First, the United States would oppose the expansion of Soviet control of nations in Europe. This was the mission of NATO.

The second strategy was to develop the capability to counter Communist-inspired wars of national liberation. The military contest in South East Asia was, in the American view, a classic conflict of this kind.

Thirdly, the United States would seek favorable relations with the non-aligned nations to slow the spread of communism. India and Nepal were two of the leading non-aligned nations at the time. The events in this story grew out of the American policies to implement the second and third strategies of its primary foreign-relations goal during the Cold War.

Scatback Mission

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, most of the tactical aircraft of the United States Air Force engaged in the War in South East Asia were assigned to the Seventh Air Force with its headquarters at Tan Son Nhut Air Base, just north of Saigon. Fighters were assigned to air bases throughout South Vietnam and Thailand.

Most fighter attacks required the pilot to identify his target visually. The most accurate weapon delivery at the time was by dive bombing. Pilots could consistently place their bombs within 100 feet of their targets using this technique on the practice range. During combat, with less than perfect weather conditions and enemy anti-aircraft fire, the accuracy sometimes decreased from that achieved in more favorable conditions.

If a pilot could not identify his assigned target visually, he had to use ground-based RADAR or a signal from a LORAN radio station. Both of these methods increased the expected miss distance between the bomb and its intended target.

For a pilot to have good visual identification of his assigned target, he needed a photograph taken from the air. The Seventh Air Force employed RF-101, RB-57 and RF-4C reconnaissance aircraft and unmanned AQM-34L Firebee drones (project Buffalo Hunter) to take pictures both before and after attacks. The reconnaissance aircraft taking pictures over the Ho Chi Minh trail in Laos and Cambodia and over targets in North Vietnam were initially based at Tan Son Nhut; then, later in Northeast Thailand at Udorn RTAFB. The drones flew out of U-Tapao RTAFB, a base in the southern part of Thailand, on wing pylons attached to DC-130 Hercules, but they were recovered post-mission in the northern part of South Vietnam, near Da Nang AB, RVN.

The officers who reviewed the aerial photographs and determined what targets were to be struck the next day worked out of the 12th Reconnaissance Intelligence Technical Squadron and HQ Seventh Air Force Command Center on Tan Son Nhut AB, in the southern part of South Vietnam.

In 1972, there was no military internet, no satellite communications system, and a very limited secure telephone network. The only way to transport the reconnaissance film to Saigon for developing and exploitation and then to deliver the correct pictures to the pilots for target study before they took off on their strike missions, was by aircraft. This was the vital military mission of an organization known as Seventh Air Force Flight Operations, code name Scatback.

Scatback employed a small fleet of T-39s, twin engine executive jet aircraft, which carried two pilots, a crew chief/flight mechanic, and six passengers. When the military demand warranted, the seats were removed to increase the courier cargo load. The reconnaissance film and mission target folders were flown between Tan Son Nhut and the Thailand fighter bases typically during night hours.

During the day, Scatback aircraft flew established routes stopping at the Seventh Air Force bases in South Vietnam and 7th/13th AF bases in Thailand where they delivered official mail, priority parts and picked up bomb damage assessment and gun camera film . Sometimes all of the seats were installed and the aircraft would ferry high level military and civilian visitors.

Flying to the Kings Funeral

After ruling Nepal for 17 years, 51-year-old King Mahendra died of a massive heart attack on January 31, 1972. Arrangements for the funeral procession were made soon after the official announcement of the King's death. Hindu religious rites and rituals do not allow the keeping of a body in state for more than 24 hours.

King Mahendra was born on June 11, 1920. He studied politics, economics, Nepali language and culture, and the English language privately in the Palace. The study of Nepali literature and composing Nepali poems also formed part of his busy life. He ascended the throne of the Kingdom of Nepal in 1952 following the sudden death of his father, King Tribhuvan. Mahendras' Coronation Ceremony was held on May 2, 1952.

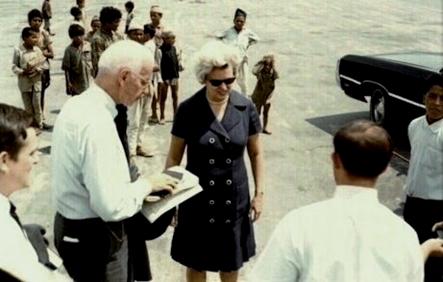

In the Nepal American Embassy the announcement of the death of the beloved king created an unusual level of concern. As it happened, the United States Ambassador to Nepal, Carol C. Laise, was out of the country. Ambassador Laise was visiting her husband in Saigon, Ambassador Ellsworth Bunker, United States Ambassador to the Republic of Vietnam.

The Laise-Bunker marriage on January 3, 1967 was the first ever between two U.S. Ambassadors. He was 23 years older than his new wife, who was 49 at the time. It was her first marriage, his second. He held the title of U.S. Ambassador-at-Large at the time of their wedding in Katmandu, where Bunker planned to make his headquarters between trouble-shooting missions around the world.

Shortly after their wedding, President Johnson asked Ambassador Bunker to take the post in Saigon. As part of the negotiation, he offered Bunker the use of an airplane to fly between Saigon and Katmandu to visit his new wife every month. (See selection from oral history account in the appendix to this paper.)

Ambassador Bunker's airplane was a VC-118A Liftmaster, serial number 51-3827.

Scatback also had two other C-118As, serial numbers 53-3231 and 53-3304; However, these aircraft were not VC (for VIP) models.

The C-118 Liftmaster was a military variation of the Douglas DC-6 commercial airliner. The VC-118 differs from the standard DC-6 configuration in that the aft fuselage was converted into a stateroom; the main cabin seated 24 passengers, or it could be made into 12 "sleeper" berths. The cruising speed was 230 knots.

The flights to and from Katmandu were popular with the staffs of the two embassies and with space available military personnel heading for R&Rs. The flights took most of a day, but the ride was comfortable, and the accommodations on board were excellent.

In those days, the communications out of Nepal were not the most reliable. In fact, there was no direct phone service between Katmandu and Saigon in 1972. Ambassador Bunker found that Amateur Radio was the only way he could communicate by voice with his wife. Utilizing a Military Amateur Radio System (MARS) station at Tan Son Nhut Air Base in Saigon, Bunker had a weekly chit-chat with his wife in Nepal.

The slow communication in the area meant that by the time Ambassador Laise had been notified of King Mahendra's funeral in Katmandu, there wasn't time to make the seven-and-a-half hour trip required by their VC-118A. The T-39, which cruised at 430 knots, would take only four hours flying time for the trip.

The T-39 Flight

Scatback T-39A, serial number 61-0675, was selected for this mission. This aircraft was the only T-39 in the organization with a High Frequency Single Side-Band (HF-SSB) radio for long range communications. It had been the dedicated aircraft for Lieutenant General Spike Momyer, when he was the Seventh Air Force Commander.

Ambassador Laise's flight to Katmandu took off from Tan Son Nhut around 0400 hours on February 1, 1972. The aircraft flew over Phnom Penh, Cambodia and refueled at Don Muang Air Base just outside Bangkok, Thailand. This leg of the flight was a little over 400 nautical miles.

The next leg of the journey flew over Rangoon, Burma and on to a refueling stop at Calcutta, India. This was the longest leg of the flight, almost 900 nautical miles. The U.S. State Department had made all arrangements for overflight approvals from the foreign nations between Saigon and Katmandu.

India had recently engaged in their war with Pakistan that led to the emergence of an independent Bangladesh. Reminders of the recent conflict--sandbag bunkers and anti-aircraft batteries--were still on the airfield. The United States had supported Pakistan during this conflict, and the presence of a United States Air Force jet with clear markings was not a welcome sight. Still, the Indian officials did not wish to delay the flight unduly--Ambassador Laise had spent eleven years in the Foreign Service as one of the State Department's top Asia experts, and she was highly respected in India. The officials settled for requiring the crew to fill out a lengthy flight plan form that included all sorts of unusual data requests.

The final leg of the flight was a little less than 400 nautical miles. The T-39 flew northwest to Patna, India and then due north to Katmandu. The distance from Patna to Katmandu is only 130 nautical miles.

In 1972, Patna was the last location with a VOR navigation radio station. Katmandu had a low-frequency, non-directional radio beacon, but the T-39 did not have a functioning ADF receiver for that type of navigation aid. The pilots depended on pilotage to find the airport at Katmandu, which means they look out the window, then look at their map, and try to find points of common identification on both.

Nepal is landlocked in a strategic location between China and India and contains eight of world's 10 highest peaks, including Mount Everest and Kanchenjunga--the world's tallest and third tallest--on the borders with China and India, respectively. Mount Everest is 29,030 feet above sea level. The T-39 pilots on this flight knew that Mount Everest was the worlds tallest peak. They did not realize that many of those other beautiful snow-covered mountains were almost as tall.

As the aircraft entered Nepalese airspace, Ambassador Laise came forward and stood between the pilots, asking, "Where are we?" The two pilots looked out the window, then at their maps, then at each other, and replied, "We do not know." {One of the pilots recently reread this section and said, "I have never been lost, I always knew where I was. I just didn't know where everything else was."}

Prudently, the Ambassador, who had made the trip many times, remained between the pilots until she sighted Katmandu down to the left. "There it is," she said and returned to her seat in the back of the aircraft.

When the pilots finally contacted the airport control tower at Tribhuvan International Airport, a crisp, British-accented voice came back on the airways, Roger, Scatback Echo. Call entering the valley. With tall mountains on all sides, the only approach was to circle down over the airport until the traffic pattern was reached. The runway was only 6,000 feet long and had an altitude of 4,390 feet above sea level. The combination of altitude and short runway was why few jet aircraft attempted to land at Katmandu in those days.

Scatback Echo was directed to park on the ramp a good distance from the main terminal. One car and a large group of local men greeted the aircraft. Many men wanted the honor of helping Ambassador Laise with her things. One lady from her staff escorted her to the waiting car, and she was off to prepare for the Kings funeral. Mission accomplished, except that the aircraft and its crew still had 1,700 nautical miles to go to reach home base in Saigon.

The airport officials provided weather information and processed the flight plan request. They followed the same procedure as the Indian officials in Calcutta, with each man in the approval chain demanding his own opportunity to examine each sheet of paper and ask his own questions, just as if he had not been sitting ten feet away in the same room while the previous official conducted his examination. In due course, the flight was approved. That is when the crew learned that the one telephone land-line to India for flight data requests was not in operation that day. Katmandu tower was willing to clear the flight to the border, but no further.

At this point the HF-SSB radio in the T-39 really proved its value. A radio call was made to Calcutta Radio, requesting flight plan approval from the Indian national air traffic control in Delhi. The request was relayed from Calcutta to Delhi via land-line, and the crew was told to stand-by. A ground-power cart was started for electrical power to keep the radio on the air. It was two hours before the Delhi air traffic control approved the flight.

During the wait, the crew allowed some of the Nepalese children gathered around the aircraft to come aboard. One at a time, each was allowed to sit in the pilot's seat with the radio headset on and wave to his friends outside. What a thrill for 8- to 14-year-old boys!

No girls sat in the aircraft. Being near the Ambassador's airplane was a privilege reserved for males only. But on the way to the end of the runway for takeoff, the crew saw a large group of women and girls waving energetically.

The T-39 arrived in Calcutta, without the Ambassador on board, and the Indian air-traffic-control delay continued. Finally, with only thirty minutes before sunset, the flight was cleared to take off. The timing of this clearance was important. The flight had to overfly the Rangoon Flight Information Region, and the diplomatic overflight approval granted to the U.S. State Department did not allow night flights.

During all the ground delay, the T-39 crew reread the Flight Information Supplement and discovered that the Rangoon FIR extended from the surface to 40,000 feet. On this evening Scatback Echo climbed to 41,000 feet, turned east high over the Bay of Bengal without a word to anyone. When the moon came up with Rangoon straight ahead and Mandalay to the left, the crew could almost hear Rudyard Kiplings famous words:

Where the flyin'-fishes play,

An' the dawn comes up like thunder outer China 'crost the Bay!

With a strong tailwind and the reduced fuel consumption of two jet engines at high altitude, no refueling in Bangkok was required. It was non-stop all the way back to Saigon.

The Flight Crew

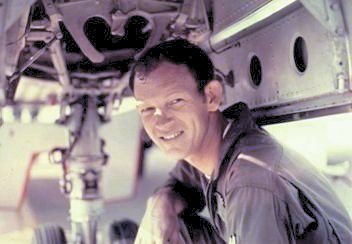

It was a flight to remember for the Scatback T-39 crew: Major Dick Miller, Major Bill Goodyear and Staff Sergeant Bobby Thrower.

When their three children were in college, Dick and his wife of 51 years, Lillian, sold their house, their cars and almost everything else they had and moved onto a 37-ft sail boat. For almost six years, they fulfilled the dream of so many as they sailed the Atlantic and the Caribbean. When Dick's mother became very ill, they sailed into Pensacola, Florida and liked it so much that they stayed. Dick became very active in the Navy yacht club and for seven years was the primary race sponsor for sail boat races.

The next adventure involved selling the boat and buying an airplane. Hurricane Ivan tried to destroy it, but with Dick's maintenance skills and help from some friends, they managed to put it back together. Its last flight came when the engine quit just after a touch- and-go-landing. Dick was over a gravel pit with trees on both sides. His landing wasn't all that good. In fact, he totaled the plane and almost bought the farm. He still hangs out at the airport and flies with friends but is not ready to get another airplane himself.

Dick and Lillian have enjoyed traveling 'Space A' to Europe and plan to do that trip again in the future. He says he is satisfied these days with just being an old, retired Air Force Vet, and "that suits me just fine, because I am with a lot of really great people."

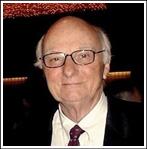

After retiring from the Air Force in 1984, Bill tried to open a gold mine in Arizona. He ended up losing his life savings and for penance worked for one year as a civilian in the Pentagon. The next year he became the general manager of a country club near Sarasota, FL. It went broke as well. Northrop Grumman, his next employer, fared better; Bill held the position of business development manager for the B-2 (Stealth) bomber for 15 years before retiring for good in 2001.

Bill and his wife, Linda, a former college professor, divide their time between Atlanta (where their grandchildren live) and Cashiers, NC (where the temperature is very livable in the summer). In 2006, after not flying for thirty-two years, Bill earned his private pilot's license. He is now teaching grandson Drew the joys of flying in a rented Piper Warrior; they fly out of DeKalb-Peachtree airport in Atlanta.

Bobby enjoyed being reunited with his wife and two children, touring the local area, and making short trips to London and Scotland. During their three years in England, the Thrower family had the opportunity to live on the local economy as well as in base housing. At the end of this time, they all returned to America, and Bobby returned to civilian life. Within two weeks, he had a job and was closing on a house.

The job that marked Bobby's civilian career was as a mechanic with the North Carolina Department of Transportation. Working on all types of heavy equipment, he became a specialist in rebuilding and testing transmissions and hydraulic systems. The Department of Transportation used his skills in all 125 of the State's shops, solving equipment problems as a Diagnostic Technician.

Bobby was promoted to manager, overseeing the work of four shops and 35 employees, but he still found time to attend night school and earn several college degrees. In the course of his career, he was often called on to do unusual jobs and to represent DOT functions and management. Once he was asked to explain the duties of a Diagnostic Technician: "I do what others can't or won't do, mostly what they won't do," he said.

Bobby Thrower is now retired, living near Raleigh, North Carolina, helping his children as they become young adults. His passion is in restoring his 1977 Dodge truck and traveling across the country. After a scare with his heart and a six-bypass surgery, he is following the doctor's orders and says he has not felt this good since leaving Scatback.

Appendix

ELLSWORTH BUNKER ORAL HISTORY, INTERVIEW I